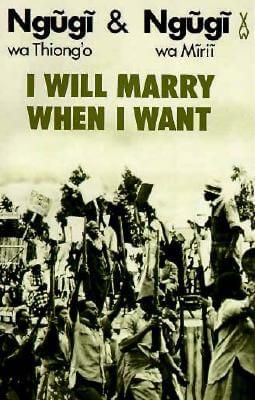

In essence, Ngũgĩ argues that this is what is happening to newly independent-or “independent,” Ngũg. Without language, passed down from one generation to the next, culture withers and dies. Thus, Ngũgĩ writes that, “Culture is almost indistinguishable from the language that makes possible its genesis, growth, banking, articulation and indeed its transmission from one generation to the next” (15). It is impossible to think about culture without thinking about language, or to think about language without thinking about culture. Though aspects are already dated, it can still serve as the basis for fruitful discussion of a subject that continues to be of interest. It addresses significant issues, and Ngugi's presentation is consistently engaging. In turn, culture “carries” particular value systems and perspectives on the self and the world. Decolonising the Mind is an interesting, if occasionally too heated (and too simplistic) work. Particular languages create and sustain-or, to borrow Ngũgĩ's terminology, “carry”-particular cultures. Language, in other words, the author argues, is cultural.

The first chapter is largely dedicated to the idea that language is not only a means of communication but also a method for carrying culture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)